|

| Pictured (1925): Annie poses in the ring with 12-year-old sparring partner Nipper Pat Daly as trainer Professor Newton looks on |

Pioneering female boxer Annie Newton is one of the many colourful characters featured in Alex Daley's book, Born to Box: The Extraordinary Story of Nipper Pat Daly (Pitch Publishing)

Today, women’s boxing is thriving. There’s never been a better time for females to take up the noble art. But what if the likes of Nicola Adams and Katie Taylor had been around in the 1920s?

Back then, their hardest fight would have been outside the ring, contending with a largely hostile society. Not only was the idea of women boxing frowned upon, it was deemed an abomination. Even leading boxing figures like the great Jimmy Wilde felt it was freakish and unseemly.

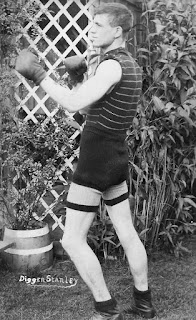

For one female boxer trying to make it in the Roaring Twenties, this ideology proved an unbeatable foe. Her name was Annie Newton and she’d been steeped in boxing from an early age. Born in Highgate, north London in 1893, she was mostly raised by her uncle, ‘Professor’ Andrew Newton, one of Britain’s top boxing trainers of the time.