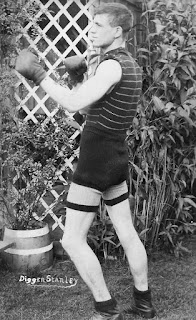

He learnt his trade on a travelling boxing booth under Billy Le Neve, the booth owner his father supposedly sold him to. Tackling men of all weights and sizes, Digger not only learnt how to box but how to employ the game’s darker arts. ‘He could break more rules, more artfully, than almost any other boxer of the past few decades,’ said his Boxing News obituary, but he was also ‘a superlatively clever boxer and ring strategist’.

With uncanny skill, speed and a hard punch in each hand, Stanley became the star of Le Neve’s booth. Whilst with the booth, he was tutored by Le Neve’s famous relative, the former English champion Jem Mace.

The earliest of Digger’s traceable bouts were in the late 1890s. In his early years, he built a formidable record, beating such notables as Owen Moran, Jim Kenrick and ex-world champion George Dixon. Stanley also laid unofficial claim to the British flyweight title.

In 1910, the National Sporting Club selected Stanley to face Salford’s Joe Bowker in a contest for the first bantamweight Lonsdale Belt. By then, Digger was well in his 30s but claimed he was 27. He had given 27 as his age for several years and would continue to do so.

Stanley and Bowker met on 17 October, the bout ending in the eighth with Joe counted out. Bowker’s corner claimed their man was fouled but since a doctor’s examination found no evidence of foul play, Digger received the verdict.

This made him the first bantamweight Lonsdale Belt-holder and by virtue of the win he claimed the world crown as well. He had two no-decision bouts in America and was offered a lucrative string of fights there, but instead returned home.

Stanley made successful title defences against Johnny Condon, Ike Bradley and Alec Lafferty, but lost his world crown in France to Charles Ledoux in seven rounds. It was the only KO loss of Digger’s career and he claimed he’d been paid to take a ‘dive’. After losing and regaining his British crown against Bill Beynon, Stanley finally lost his title to Curley Walker, having won a Lonsdale Belt outright.

Digger’s final years were sad ones. Although he had earned some big purses, his penchant for gambling saw his ring money quickly slip away. By his late 30s, he had damaged hands and had shattered one of his thighs in a trotting-race accident, leaving one leg shorter than the other. He was no longer fit to fight but had little choice. He had a family to support and boxing was all he knew. Rather than be KO’d by younger, fitter men, Digger employed the roughhouse tricks he’d learnt on the booths. Consequently, the tail-end of his record is dotted with disqualifications.

Stanley died in poverty, in March 1919, seven months after his final fight following a long illness. His age at death was officially recorded as 42, but this was just an estimate.

Article © copyright Alex Daley.

This piece by Alex Daley (first published in Boxing News on 1 March 2018) is one of 132 articles featured in the anthology Boxing Nostalgia: The Good, the Bad and the Weird. You can find out more or buy a copy here.